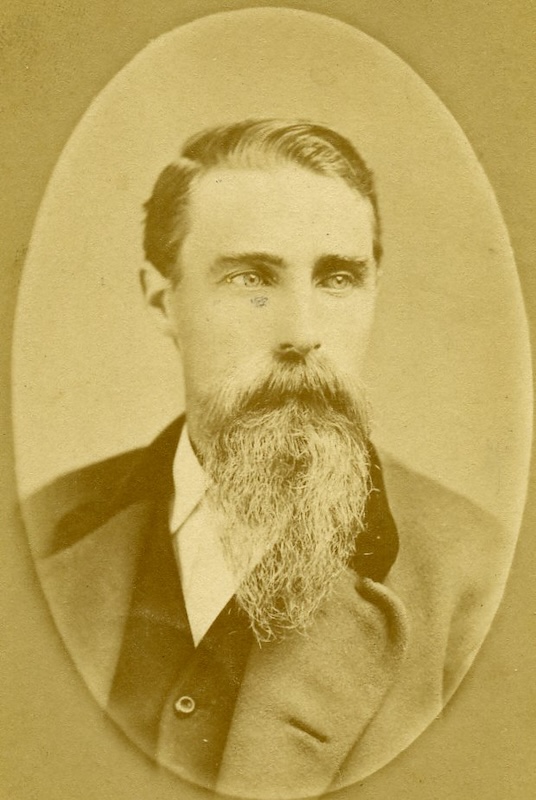

Studio portrait of Thomas Dollard, c. 1875. (Gift of Hazel Jarvis Edwards)

[This article was originally printed in the Mendocino Beacon on February 7th, 2013.]

On October 15, 1879, the Beacon reported that Mendocino had been “…thrown into a state of excitement hitherto unparalleled by the occurrence of a shocking calamity….Two of our most esteemed citizens were atrociously murdered and a third wounded within four miles of our town, their comrades narrowly escaping death.” The victims had been deputized to track down rustlers. Cattle had disappeared from a herd belonging to the Mendocino Lumber Company, and the slain men rode into a trap set by killers who became known as the Mendocino Outlaws.

The tragedy began when Constable William Host rode into Big River Woods in search of evidence. He discovered the remains of a half-buried steer, and the next morning Host returned with two deputized lawmen to investigate further. They spotted tracks and followed them to an encampment where four men lounged around a fire eating breakfast, beef curing in plain sight. Also in plain sight, resting against a redwood, were Winchester rifles, pistols and abundant ammunition.

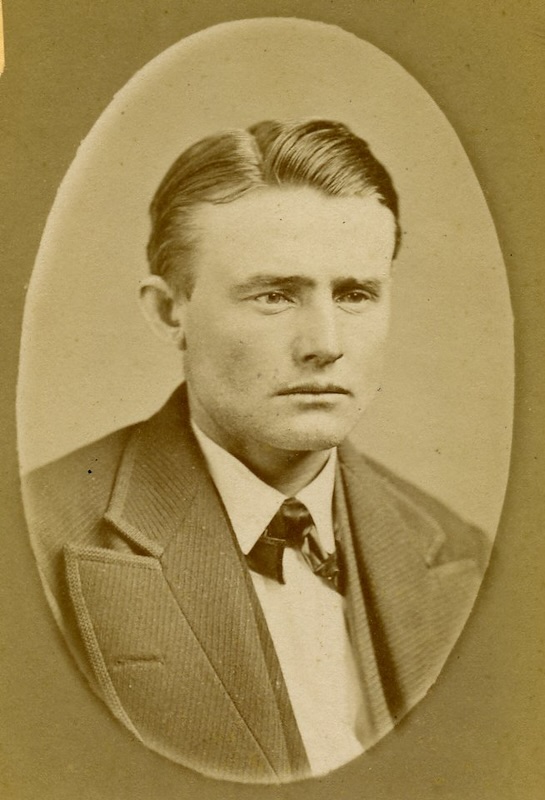

Host had no warrant. He feigned ignorance of the area, inquiring if the men knew of another good place to set up camp. The Mendocino Outlaws weren’t fooled: they knew who Host was and prepared to wait for him for their real motive was to rob him of the taxes he would be collecting. Back in Mendocino, Host deputized a posse and set out the next morning with seven men. Among them rode 31-year-old James Nichols, a veteran of the Civil War from Ellsworth, Maine. He had come west after the fighting and taken employment in the logging industry, working his way up to superintendent at the Mendocino Lumber Company.

Nichols wasn’t the only Maine native in the posse. Thomas Dollard came from Ellsworth, too, and he and Nichols were likely childhood friends. Dollard had left logging to join with yet another Maine native, Henry Jarvis, to open a thriving, merchandising venture on the corner of Kasten and Main Street.

Perhaps as they rode, the men chatted about business or the rumor of Dollard’s engagement to Katherine Carlson, “One of Mendocino’s most popular young ladies.” She was the 19-year-old daughter of Charlie Carlson, a big Swede who owned one of the most respected hotels in Northern California. His twin daughters, Katie and Bessie, did everything in tandem, including run the hotel’s popular dining room.

Studio portrait of James Nichols. (Gift of Nannie Escola)

According to Lyman Palmer’s “History of Mendocino County,” the posse found the first camp abandoned. They tracked the bandits along Big River Ridge until they located a second camp deep in a ravine about a mile from the first. They worked their way down a steep precipice and dismounted to investigate. William Wright was in the lead. He bent over the ashes of an abandoned fire. According to Palmer, his final words were, “They must have stopped here last night.”

The outlaws, positioned in the burnt-out trunk of a massive redwood, fired from the opposite side of the gully. Wright took a bullet to the back of his neck as dozens of shots rang out in rapid succession. Only four of the posse made it to cover. Among those who didn’t were Dollard and Nichols. Dollard took a bullet to his thigh, returning fire as he fell back. Hit twice more, he rolled to the bottom of the ravine where he managed to crawl under a log in the creek. Nichols took a bullet to his shoulder, but made it to his horse. He and another man got away and rode for help. By the time help arrived, however, Dollard was dead, and Wright close to it.

Nichols and Wright were brought to the Carlson Hotel to have their wounds looked after. Wright had taken a second bullet near his heart and remained “helpless and speechless.” He died the first night, his body removed to a room over the post office where Dollard had been taken. Nichols survived, perhaps because he was nursed back to health by the Carlson twins.

Two well-armed parties set out that same evening, and the next day more men joined the hunt. Within a week the governor had offered a reward: $300 for the first, and $200 for each subsequent killer. It took a manhunt of 61 days over much of Northern California before the shooters were found and brought in.

Two and a half years after the attack, James Nichols joined Henry Jarvis in the general store and married Katie Carlson. Their daughter, born the following year, was the beautiful Edith Nichols, the apple of Auggie Heeser’s eye. But that’s another story.

The Kelley House Museum is open from 11AM to 3PM Thursday through Monday. If you have a question for the curator, reach out to [email protected] to make an appointment. Walking tours of the historic district depart from the Kelley House regularly.