Excerpt from Mendocino Historical Review Vol. XXVI, Summer, 2012. “Belonging to Places: The Evolution of Coastal Communities and Landscapes between Ten Mile River and Cottoneva Creek.”

The remoteness of the northern Mendocino County coast has for most of history demanded self-sufficiency of the people who have made their homes here. V. K. Chestnut and Edward Gifford discuss long lists of native plants harvested by indigenous peoples in the local area. Chestnut was a botanist who published Plants used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California in 1902. Gifford was an anthropologist at UC Berkeley whose ethnographies of California tribes were rich in detail. Both interviewed tribal people about their knowledge of local plants, mushrooms and seaweed, and how they were employed: food, medicine, basketry, cordage, and clothing. They also learned about the widely used practices of burning, pruning, and seed distribution.

Chestnut described how acorns were harvested and prepared. When they were ripe in the autumn, the men went and beat them off the tree while the women collected them in large conical carrying baskets. About 500 pounds were collected by each family, with the nuts dried in the sun, and then stored in special granary structures built above the ground on poles with loosely woven sides to allow air flow. The Coast Yuki stored them in conical baskets or on a shallowly sloping roof covered with slabs of redwood bark. Care was taken to prevent mold by drying the crop thoroughly.

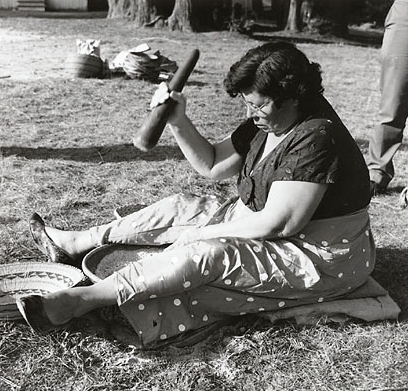

Essie Parrish demonstrating the traditional method of pounding acorns into meal, 1960. Subsequent to pounding, the meal was leached of tannin with water in preparation for consumption.

To prepare the acorns for eating, the tannin had to be removed by leaching with water. The nuts were ground into a fine powder. A basin was then dug in a sandy area near a stream to receive the flour. Water was poured over the flour about a dozen times to remove the bitterness. The meal was removed by hand, with the final part placed in a basket with water to allow the sand to settle out. The leached meal could be prepared in many ways. Buckeyes were cooked by covering them with hot stones and then mashed. The nuts of the bay laurel (pepperwood) were also cooked in hot ashes and cracked open to eat.

Blackberries, huckleberries, wild strawberries, madrone berries, and rose hips were collected and eaten raw. Manzanita berries and the yerba buena plant (the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants in the mint family) were both made into cider. Seeds of various plants were collected using a basket and seed beater while walking through a field. Several root crops like blue camas bulbs and wild onions were also gathered.

Mushrooms that grew under oak and madrone trees were eaten by the Yuki, although the species they took are uncertain. Chestnut reported the Native Americans were superstitious about some edible varieties that were collected for sale to settlers. James McGrew recalled collecting large numbers of mushrooms in the fields around Westport, with a particularly heavy crop in 1933, after the spring rain. They were probably the genus agaricus, which are common open-field mushroom species related to the variety sold commercially in grocery stores today. The yields of field mushrooms dropped radically, however, when pigs were turned loose in the fields in later years, according to McGrew. Even today, mushrooms, including chanterelles, boletes and hedgehogs, are collected for personal use or sold to local buyers as a cash crop.

A well-known Hopland Pomo weaver and elder, Elsie Allen, told Tooker on September 12th, 1965 that sea palms and bullwhip kelp were collected for food. In the later 1800s, they dried and sold large quantities to Chinese buyers.

Allen also told Tooker about the intertidal animals that were eaten by the Pomo when they visited the coast. Both fish and shellfish were dried on boards or smoked to preserve them. Surf fish were caught with fiber nets, while salmon were speared in local streams during their winter run. There is no archaeological evidence that local Native Americans caught ocean fish, but they did hunt many kinds of marine mammals for food.

Many practices of the settlers changed the availability of plants and animals used for subsistence by Native Americans. Widespread harvests of tanbark oaks decimated the acorns that were a traditional staple for the local Native American population. The newcomers also reduced herds of large game animals including deer and elk, as well as top predators such as mountain lions, bears, and bobcats. Contemporary historian Benjamin Madley writing about the Round Valley Yuki (in An American Genocide) notes that settlers took over the lush meadows for grazing lands and agriculture and “settlers’ hogs, cattle, and horses set out to pasture in these areas consumed to the core of the Yuki diet. Further, the settlers’ domesticated animals drove wild game away from prime grazing areas thus depriving the Yuki of meat.”

The Kelley House Museum is open from 11AM to 3PM Thursday through Monday. Visit the Kelley House Event Calendar to schedule a Walking Tour of the Historic District.