Reprinted from the February 25, 1993 Mendocino Beacon and annotated with additional information.

Caspar Creek, and later the town of Caspar, were named after Siegfried Caspar, an early settler of German descent who raised cattle in the vicinity. Construction of the sawmill near where Caspar Creek meets the ocean commenced in 1861, after the owners, William Kelley, Captain Richard Rundle, and Eugene Brown purchased 5,000 acres of timberland around Caspar Creek. This was almost ten years after the start of the Big River mill in Mendocino, but the Caspar mill was the first one on the coast to construct its own railroad.

By the late 1860s, the supply of lumber in the Caspar Creek area was dwindling; mill owner Jacob Green Jackson, who had bought out the original owners in 1864, purchased a large tract along the next creek to the north, Jughandle Creek. While the logs from the Caspar Creek area could be floated down to the mill, the logs from the Jughandle Creek area would have to be moved up and over the ridge separating the two creeks, or a new mill would have to be constructed on Jughandle Creek. Jackson decided that the most cost-effective solution was to build a railroad to bring the logs to the Caspar Mill.

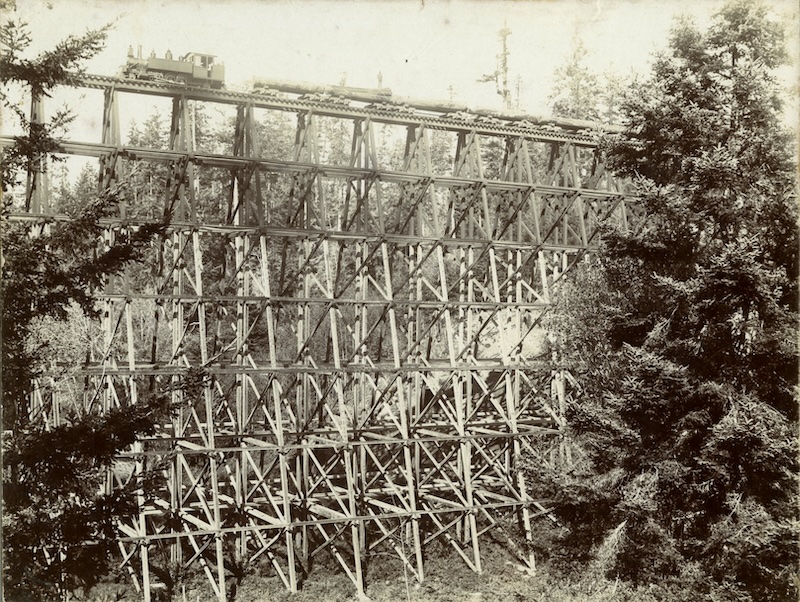

Log train crossing the Jughandle Creek trestle.

The railroad was constructed in 1869 and 1870, with wooden rails covered with thin iron straps. It was about one mile long [and ran roughly where Highway 1 is today]. Flat railroad cars with flanged metal wheels were made to carry the logs. Oxen dragged the logs to and onto the cars, then horses and mules pulled the cars to the mill. There was a dam across Caspar Creek next to the mill, which created a millpond for log storage. The logs were rolled off the cars and then slid down a chute into the millpond.

By 1875 the railroad had been extended quite a bit further up Jughandle Creek, to a distance where animal power was no longer adequate. A steam engine made by the Vulcan Iron Works in San Francisco was brought north via ship, disassembled, and the pieces were barged ashore where they were reassembled, but the new engine, named “Jumbo,” proved too heavy for the strap iron rails. Fortunately, a large quantity of solid iron rails were acquired, salvaged from a shipwreck off the South American coast.

[In 1882, the Mendocino Beacon reported, ”At Caspar, the Jug Handle railway makes six or seven trips daily. The railway, or properly speaking, tramway, extends 5 miles in the woods, so there is a distance of nearly 70 miles traversed each day. The output is between two and three hundred logs.”]

By 1884 Jumbo, now called “Old Dirty and Greasy,” had pushed or pulled a great quantity of logs out of the Jughandle Creek area and more timberland was needed. A huge tract was purchased this time farther north, covering nearly all of the Hare Creek watershed, an acquisition that was key to the long success of the Caspar Lumber Company.

Bringing logs to the mill from this new territory required crossing Jughandle Creek, and that required building a large wooden trestle [about a half a mile upstream from where the highway bridge is now]. In 1885, Jackson brought in engineers and bridge builders from the Central Pacific Railroad to create the Jughandle Creek trestle. It was 7000 feet long, 146 feet high, 82 feet wide at the base, and 12 feet wide at the top. It consisted of seven 20 layers or “bents,” each 22 feet high and 10 feet wider at the base than at the top.

At that time it was one of the largest and tallest structures of its kind, and immediately became a favorite spot for photographers. There was no roadway on top, only rails and ties, so it was a scary business walking out on it. Yet people did, and had their pictures taken as testimony.

The earthquake of 1906 caused the trestle to “collapse like a row of dominoes,” but it was quickly rebuilt following the original specifications. Later, the Caspar Lumber Company acquired nearly all the timberland around the south fork of Noyo River. Between 1884 and 1945, nearly all of the logs that came out passed over the trestle, pulled by Jumbo or one of its seven successors.

[The trestle remained in operation until 1945, and was dismantled after the railroad was abandoned in favor of truck transport, according to the Jug Handle State Natural Reserve brochure from California State Parks.]

Thanks to Ted Wurm and his wonderful book “Mallets of the Mendocino Coast,” for much of the above.

The Kelley House Museum is open from 11AM to 3PM Thursday through Monday. Walking Tours of Mendocino are available throughout the week. Visit the Kelley House Event Calendar for a Walking Tour schedule.