People living before the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics or even antiviral medications, which we take for granted, were no strangers to death. However, the influenza pandemic, which came in the wake of the end of the First World War, occurred on a scale so devastating that it took more victims than had the Great War itself. As we cross the threshold of 2018, the centenary of both the conclusion of WWI and the influenza epidemic, it is perhaps fitting that we revisit this topic.

People living before the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics or even antiviral medications, which we take for granted, were no strangers to death. However, the influenza pandemic, which came in the wake of the end of the First World War, occurred on a scale so devastating that it took more victims than had the Great War itself. As we cross the threshold of 2018, the centenary of both the conclusion of WWI and the influenza epidemic, it is perhaps fitting that we revisit this topic.

Influenza arrived on the Mendocino Coast in the fall of 1918 and did not clear out until the early months of 1919. Mendocino was hit first, followed by Fort Bragg. Then as now, many people had family members or friends living in the larger cities, such as San Francisco and Oakland, where conditions aiding transmission of the disease meant that there were more cases.

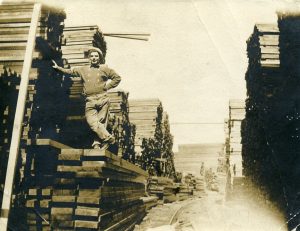

Others have written volumes about the pandemic, but in 2006 a Mendocino High School student, Gabriel Tallent, tackled the subject of influenza in his own community. Mr. Tallent’s student paper was largely based on reporting done for the Mendocino Beacon at the time. He noted that the first victim of influenza on the Coast was John James Brown, son of John Q. Brown, and a native of Mendocino. John J. Brown died at the age of 34 and had worked as a tallyman for the Mendocino Lumber Company. His date of death, October 23, 1918, puts the arrival of the influenza virus on the Coast at about a week before Halloween that year. Another death occurred on the same day, in Willits. That was William Bergerson, age 28, who left a wife and two children behind.

One of the observations made at the time was the seemingly odd fact that this flu’s victims were frequently young and otherwise hale and hearty people. The reason for that may have been related to the strength of one’s immune system. Ironically, the stronger immune systems caused an overreaction of the body to the flu, intensifying symptoms and making it harder to recover. This was hypothesized by researchers who recovered the virus (H1N1) from frozen bodies of its victims (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1918_flu_pandemic).

Gabriel Tallent’s high school paper described Mendocino’s reaction to the epidemic, which mirrored that of towns and cities all over the world. The relative low density of the population on the Coast likely worked favorably for its mill town communities. People still died, despite the precautions of closing schools, postponing the Apple Fair, closing theatres, distributing masks made by townswomen (and sold for seven-and-one-half cents each). The Preston home was opened as a Red Cross Hospital, with graduate nurses recruited to tend approximately twenty patients. The crew of the steam schooner, Sea Foam, had to dock the ship in Mendocino temporarily, as they were too ill to put to sea.

Of course, the toll exacted by influenza on its victims had repercussions that would be felt beyond the worst months of the epidemic. One story told of the death of Mrs. N. Bortolomei of Fort Bragg, who left a family of three small children behind for her husband, Roberto, to raise. The youngest, five month old Anastasia, was adopted by Fort Bragg’s city attorney, Leonard Stone, and his wife, Helen Stone. They renamed the baby girl Elizabeth.

Photo caption: John James “Uncle Johnny” Brown at the lumberyard