If you want to see three words together that might clash with each other, try “logging camp” and “cute.” But I don’t care what anyone says, if you look at logging camp cabins being transported on railroad flat cars they are CUTE.

When logging operations a century ago were miles from mills or towns in roadless areas only accessible by logging railroad, getting loggers to their workplace was a challenge. Lumber companies learned if you built a tiny village out in the woods, with all the services needed, you could keep loggers out in the woods for the work week (or longer) and not lose valuable time transporting them back and forth.

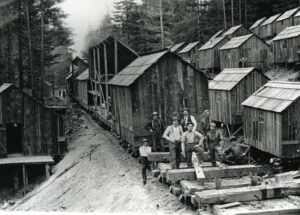

Logging camps were established in Mendocino and Humboldt Counties. For bachelors, there were shared cabins, also called shanties, 8 to 10 feet wide and 15 feet long, with a door and windows. Inside would be cots or bunk beds, a mattress pad, a wood stove, and hooks for clothing.

The cabin size was dictated by the necessity of moving them on the lumber company railroad. This was portable housing long before the current fad for “tiny houses” was created. Once the timber around a logging camp was harvested, the whole camp moved to a new timbered location down the tracks someplace. Moving days for a trainload of cabins attracted photographers because it was such an unusual sight. Such photographs shown to East Coast investors would allow the timber company to show how resourceful they were. They didn’t waste money building cabins over and over, they just moved them around.

Cabins for the men could be pulled onto flat cars. Bigger houses for families, camp service buildings, even schools, were built as units that could be joined together once back on the ground in a new location. Old photos show one half of an office, or cookhouse, or saw-filers shack, headed down the tracks with the other half on the next flat car.

Along with the housing and service building already named there was the store, the blacksmith shop and machine shop, bath house, electric power plant, outhouses, and if the camp was lucky, a dance hall.

The Union Lumber Company, Mendocino Lumber Company, and timber companies in Casper, Albion, and Greenwood/Elk all had portable housing units for logging camps. A sad photo, to this historian, was an abandoned Navarro Lumber site years after the mill closed and all the little cabins were still lined up waiting for loggers who would never return.

Mill sites used the same idea to provide mill workers with a roof over their heads. Camps were common from the late 1800s into the 1930s when moving logs by truck, not railroad, became common. Hammond lumber in Humboldt County moved camps around Big Lagoon and Union Lumber Company had camps in the Ten-Mile River drainage.

When a logger was in camp, he was worked long hours, ate in the cookhouse, and waited for weekends when the train would take the loggers to town to drink, party and have a good time. The train back to camp Sunday night was called the “Drunkard’s Special.”

A last visible link to these portable logging camp days is visible at Camp 20, a rest area now along Highway 20. There in the trees is a little red schoolhouse, and if you look carefully at it, you’ll see it’s made in three sections. The school could be taken apart and moved with cabins to the next logging camp by train.

More historical photographs can be viewed at the Online Collections tab on the Kelley House Museum’s website. https://mendocinohistory.pastperfectonline.com