Libraries Arrive on the Coast

Looking at how libraries arrived on the Mendocino Coast is part of an on-going series exploring the growth of libraries. This week’s story is part two and is a peek into the importance of fraternal organizations and a bookmobile.

Fraternal organizations gave a sense of “family” to newcomers arriving on the coast. They could be based on religion, language, politics, educational goals, military service, social views and more. Many survive to this day. The Masonic orders, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, the Loyal Order of Moose, Redman, and Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West are still with us. Many of these groups had “Reading Rooms” – the precursors to our libraries.

Mendocino City, with a huge Azorian Portugese population, had Uniao Portuguesa Protectore Do Estrada (UPPEC), Concelho Estrela Do Norte (IDES) for the men and Socieda Portuguese Rainhe Santa Isabela (SPRSI) for the women. Add in a Croatian Society, Knights of the Maccabees, Mendocino Grove of Druids (UAOD) which had groups in Willits, Point Arena and Elk, and the Knights of Pythians and reading rooms may have abounded.

The owners of lumber mills liked these groups because brotherhood gatherings kept men out of saloons. If a mill owner was in favor of prohibition, he encouraged membership in the International Order of Good Templers who were against liquor. The men’s wives could join the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Such was the power of these groups that Mendocino City voted to go “dry” in 1909, ten years before the rest of the nation did so.

The Templars mentioned above had a “Reading Room” in their meeting lodge in a long gone building across from the Mendocino Hotel on Main Street. A future column will explore the growth of libraries in Mendocino City. And wait until you read how Girl Scouts were involved.

The Kalevala Lodge for Finnish people in Fort Bragg had a library and shared “Tyomie” newspapers, printed in the USA with news in the Finnish language. This writer’s family included Kalevala Lodge members and has a Finnish-English dictionary that may have been part of that library. Inside the front cover were written the most important words like rent, wages, contract, and insurance – words immigrants needed to learn in English right away.

The inland towns of Willits and Ukiah were gifted with “Carnegie Libraries” by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie and both still stand, but even these “free” libraries charged yearly dues. It was not until the 1960s that the idea of a county library system loaning free books emerged thanks to a bookmobile.

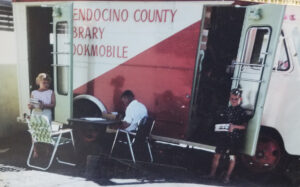

Library supporters and politicians had been trying to get the voters to support library services for years without luck. But in 1962, a National Library Services Act grant was received that funded a “Service Demonstration Project.” Its bookmobile drew from a 7,000-book collection (not open to the public), and had space on board for 1,500 books, a driver, and a librarian.

At its first stop in Redwood Valley in June 1962, the Ukiah Daily Journal reported that the bookmobile was greeted by a line of people stretching for a city block, all wanting books. The stop, scheduled to last one hour, lasted three and a half hours and 238 books were checked out. The bookmobile was a hit wherever it went and still is.

A key part then, and to this day, is the idea of a cooperative library system. Rather than duplicating effort, one library does the ordering, processing, communication and distribution of materials. This saves time and money. With the introduction of a bookmobile, the county voters approved of the idea of a library system. In future weeks we’ll explore how libraries grew on the coast.