Whether you have lived on the North Coast for a lifetime or you are just passing through it is clear that this part of the world, with all its attendant beauty, can be a dangerous place. The early days were marked by various accidents, many of which happened in the context of the lumber industry. Inside the mill near whirring saws and slippery belts, working the mill pond, or out in the woods falling and transporting trees, there were multiple opportunities for things to go wrong in a hurry. The difference between then and now is that we have taken steps to put some safeguards in place and transport to a hospital has been improved.

Whether you have lived on the North Coast for a lifetime or you are just passing through it is clear that this part of the world, with all its attendant beauty, can be a dangerous place. The early days were marked by various accidents, many of which happened in the context of the lumber industry. Inside the mill near whirring saws and slippery belts, working the mill pond, or out in the woods falling and transporting trees, there were multiple opportunities for things to go wrong in a hurry. The difference between then and now is that we have taken steps to put some safeguards in place and transport to a hospital has been improved.

Researchers at the Kelley House can consult a subject file devoted to the topic of “Accidents.” It is filled with photocopies of clippings from the Mendocino Beacon and includes stories which date back to the 1880s and forward to the 1950s. Page after page of stories can be read about accidents occurring while men were working in the woods or at the mills. Encounters with the ocean resulted in numerous incidents where lives were lost while fishing or collecting abalone or mussels. Even a bucolic day boating with friends on Big River could end badly. Before the advent of automobiles, stage and buggy accidents frequently filled the columns of the local papers. Bridge and road builders worked to make these less common, but it became apparent that drivers of autos on the highways were certainly not immune to mishaps.

One of the items in the archive of the Kelley House Museum is a journal belonging to Carolus Malcolm Walker (1862-1947), who served as Justice of the Peace and coroner for the township of Cuffey’s Cove in the early years of the twentieth century. C.M. Walker was elected judge in 1906 and was reelected nine more times before his eventual resignation in the 1940s. Wikipedia, the well-known online encyclopedia, defines coroner as:

“. . . a person whose standard role is to confirm and certify the death of an individual within a jurisdiction. A coroner may also conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner’s jurisdiction.”

The journal records the results of inquests regarding the deaths that occurred in Walker’s jurisdiction, when there was some doubt as to the cause of death. The possibility of “foul play” had to be eliminated. Mr. Walker’s records provide a glimpse into the cases he handled.

One example involved a man not known to many, who had recently taken a job at the mill in Greenwood. The death of Joseph O’Day, estimated to be of an age of 35 years, happened on April 12, 1909, as a result of drowning in the mill pond, where the depth of the water was judged by one witness to be only five to seven feet. Members of the jury for the inquest included William Dougherty, foreman. After being sworn in, questions were asked of witnesses concerning the man: whether he was known to them, when he was last seen, etc. For the most part, the witnesses’ testimonies corroborated each other. They stated that the deceased had not been known to have quarreled with any fellow worker.C. E. Benjamine stated that Mr. O’Day, deceased, had started working on the 9th of April.

The first sign of trouble was the sight of the dead man’s hat floating on the pond’s surface, near where he had been working sawing logs. They used grappling hooks to get him out of the water. Dr. A. C. Hunnley, who had been called out to the mill pond by telephone, had arrived as quickly as possible (a duration of about one half hour). The doctor saw that the men had put the drowned man over a barrel, which they were rolling, in an attempt to revive him. The doctor stated that no wound severe enough to produce unconsciousness was noted on the body, and that the man was dead by the time he got to the site. The doctor was asked “You did all you could to revive him did you not?” He answered, “Yes and failed.”

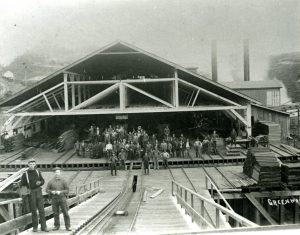

Photo caption: Greenwood Mill at Cuffey’s Cove, circa 1882-1897. Workers unidentified.