Last week I did my citizen’s duty and completed my response to the 2020 Census using just my phone, while sitting on the sofa. So easy. It took less than 10 minutes. I enumerated myself.

This got me thinking about how counting everybody correctly used to be a really hard thing to do. And who, I wondered, did the enumeration back then? Whoever they were, the people who agreed to spend a month or two riding on horses all over the county, traveling down every wagon road or trail, visiting every dwelling, camp, hut, shop or mill, would have had to be rather remarkable folk. With good handwriting.

Early enumerators took a qualifying test, and if they passed, they would swear an oath of office before a judge that they would perform their important task in very specific ways and receive no bribes or offers from others to adjust the count. They were given supplies, such as maps and portable inkstands, as well as a small booklet on how to fill out the large preprinted blank forms they carried with them.

Each form had 40 to 80 lines where the enumerator entered each person and their particulars. From census to census, the information that was requested changed, depending on what the government was interested in, but the basic population information was all about who lived in each household: their names, gender, race, age, and relationships.

The new state of California’s 1849 constitution dictated that a state census be taken in 1852. Mendocino County’s was made by George Story, a single 28-year old watchmaker from New York City. It took just 4½ pages to list the names of the county’s early inhabitants.

The first person he recorded was Deavenport Coggens, a 30-year old farmer from New York and his family. And look! we see William H. Kelley, age 28, occupation “Carpenter” and also Edwards Williams, a 32-year old merchant from New York (for whom Williams Street is named).

George the enumerator displayed some creative spelling: the state of Iowa was written IOWAY – perhaps the way it was pronounced back then? He also described various occupations as MASHENISTS, CUPPERS, ENGENEARS and CUCKS.

James E. Pettus performed the next federal census for the Big River Township in 1860. Pettus was a 32-year old Virginian who would soon register for the Civil War draft and fight on the Union side. He had horrible handwriting.

The instructions from Congress at this time said that Assistant Marshals, which is what enumerators then were called, must be residents of the district or township to which they were assigned – no hired guns, so to speak. They were paid at the rate of $1.25 per thousand persons, but not less than $250. There was an additional 10 cents given for each farm return, 15 cents for inventorying places of productive industry, 2% for gathering social statistics, and for each deceased person noted they would receive a 2-cent bonus.

The 1870 count was done by M. J. C. Galvin, who would soon become the publisher of the West Coast Star newspaper, the immediate predecessor to the Mendocino Beacon. He would go on to be elected Justice of the Peace for the Big River and the Arena Townships, then became a coastal attorney, real estate broker and sawmill developer. His clear handwriting filled 41 pages, and encompassed Mendocino City, Little River, Albion and Navarro.

These first three censuses contained many Indians. The 1852 one simply recorded the 187 “domesticated” males and females, but in 1860 we see three pages filled with the 111 Anglicized names of the native population. The occupations of both men and women are listed as “Apprentice.” In 1860, more than half of the Indians living on the coast could read and write English.

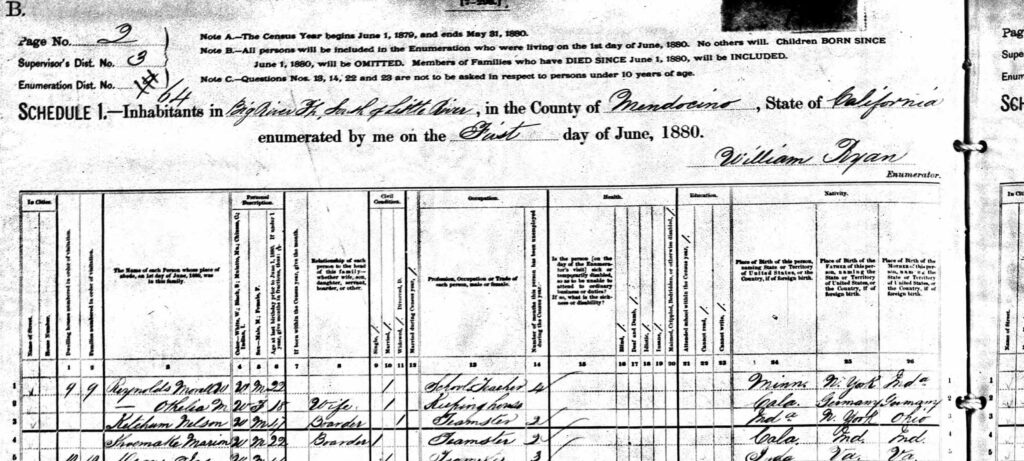

By 1880, Big River’s growing population count was divided into two districts which required a second Assistant Marshal to complete the job in the allowed time. One district was enumerated by William Ryan of Christine/Philo/Boonville, who was renowned for his mathematical skills and was a walking encyclopedia of California history.

The other was done by Alfred Nelson, Jr., the 36-year old Constable for Big River Township. Alf collected taxes, served warrants, arrested people and took them to jail in Ukiah or escorted them to the insane asylum in Napa. He also played bass drum in a 7-piece brass band and organized masquerade balls for the entire town. A fun guy.

Alf and William found that Big River Township had about 2,500 people in 1880, compared to 800 people in Ten Mile township to the north and 1,200 in Arena township to the south. In this count, the local Indian population dwindled to just 44, almost none of whom could read or write. More Chinese people were listed, including Chung Kow who had a laundry at the corner of Kasten and Main, where Out of This World sits now.

There is no 1890 census available because all copies of it were destroyed by fire and flooding.

The 40-page 1900 count was also accomplished by two men. Forty-three-year old Otha L. Stanley was a printer and newspaper man who had worked several years at the Beacon. He owned half interest in the Republican Press and was later an associate editor for the Dispatch-Democrat. There was also Ralph C. Greenough of Little River, a 22-year old teacher and educator who attended Miss Porterfield’s normal school in Ukiah and was later principal of the Mendocino Grammar School and then the Fort Bragg School. He died at the age of just 37 from tuberculosis of the throat.

The 1910 census was done by two second-generation Mendocinoans – William True Wallace, Jr. and Oscar Everson. Billy had been born 33 years previously in the Navarro Lumbering Camp and came to Mendocino with his family as a young person, living on Covelo Street between Ford and Lansing with his wife Nellie Bowman and her two orphaned younger brothers. He was always interested in lumber and the shipping trade. His father, a well-regarded Justice of the Peace for many years, lived next door.

As for Oscar, he grew up in his father Abram Everson’s general merchandise store on Main Street (where Twist is now located) and learned to be a telegraph operator at an early age. He went on to have a successful career with Wells Fargo & Company, and the Market Street Bank in San Francisco. In 1910, we find him back in his hometown, now 54 years of age and living on Albion Street behind his old store.

For the 1920 census, another older man was engaged – 52-year-old retired attorney John F. Murray. He had grown up in Mendocino, the son of pioneer druggist J. D. Murray and Theresa Flanagan. John was elected Justice of the Peace at Mendocino in 1903 and served until 1910 when Judge Wallace (Billy’s dad) stepped in. John resumed that post in 1922 when Judge Wallace died and kept it until he resigned in 1937.

The other enumerator was Andrew Escola, a 39-year old Finnish-born farmer. He was related by marriage to local historian Nannie Flood Escola. Indeed, Miss Nannie’s name is noted on the previous census as a boarder with his family when she was a teacher. Andrew was appointed to fill the post in a strange way, after enumerator William Duchrau died suddenly in the car while driving back from census instruction at Ukiah with John F. Murray.

John F. Murray, now 62, came back for another round as census enumerator in the 1930 census, along with Walter A. Jackson, a 40-year old woodsmen, local historian and author who lived in a home he built on Jackson Street, just east of Highway 1 in Mendocino. The three districts they counted that April included the families living in lumber camps, such as the well-known Boyle’s Camp on Big River, which later became the Mendocino Woodlands Park.

Unlike previous counts, the 1940 census was not done by long-time residents who knew the environs and its people, but by newcomers, such as U. S. Coast Guardsman Thomas A. Atkinson, who had been posted at other light stations up and down the coast. He needed just 16 lines to register the names of the three Point Cabrillo Lighthouse Keepers’ families under his watch. The rest of the 1940 census was completed, for the first time, by women.

Clara Ellen Reeves was a 54-year old housewife, born in Minnesota and married to Chauncy “Chance” Reeves from Michigan, a mechanic with the Mendocino Woodlands Park project in East Mendocino. They lived on Pine Street near the Chester Walbridge family. While she had only an eighth-grade education, her handwriting was very readable.

1940’s third enumerator was 33-year old Janet N. Bennett who, surprisingly, appears to have been Clara Reeves’ daughter. She too was born in Minnesota and was married to Sydney Claude Bennett from San Francisco. Both had gone to college, but by this time, at the end of the Great Depression, he was working as an attendant at a Caspar gasoline filling station, and she was a cook.

The 1940 census is the most recent one available for public use because of a statutory 72-year restriction on access for privacy reasons (72 years is an actuarial lifespan). The 1950 count will be released in 2022.

Still, an enormous amount of more current data regarding Mendocino and its people can be viewed at the Census Office’s well-designed website www.census.gov. While this is very helpful information, it is aggregated, impersonal data. The 1940 and earlier censuses, with the individual names, age, gender, race, education, and place of birth as well as a host of other revealing facts, are a remarkable resource that does much to bring our coastal history to life.

While the Kelley House Museum and Research Office is temporarily closed until further notice, please visit our website where you can view our latest digital exhibit, “South Of Main,” as well as enjoy hours of historical photos and descriptions in our online collections https://mendocinohistory.pastperfectonline.com/

If you enjoy using our resources, we would greatly appreciate a donation to our private non-profit organization during these times when income from our museum and walking tours has been eliminated. Be safe!