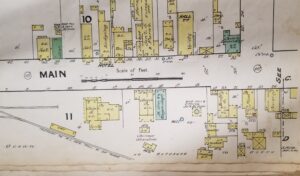

For the current exhibition concerning Chinese on the Mendocino Coast, the Kelley House Museum has set out in a glass display case a large book of maps that shows what Mendocino City looked like 130 years ago. This is the 1890 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, one of the riches resources we have for showing what things were like back in the day. Its pages contain the outlines of saloons, houses, stores and stables, all drawn to scale and labeled.

If you look closely, you’ll see some of those handwritten labels note where the Chinese people lived and worked, as the late 1800s was a period of time when this population was of special interest to Californians. There were five places around town where clusters of buildings were shown as “Chinese” — on Main, Kasten, Albion, Lansing and Ukiah Streets. Mendocino City’s main “Chinatown” was west of Kasten Street on the south side of Main, but we were not the only small community in California with an Asian area.

The Chinese had been on the west coast of North America for some time as adventurers, priests and merchants. In fact, there were early Chinese immigrants to Mexico before those in California, and a number of Chinese were in California during Spanish rule, according to the book Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California, published by the National Park Service.

But it was the Gold Rush that really swelled their numbers. My research revealed 54 men arriving by boat in 1849, 789 men in 1850, and then a huge leap of 4,018 men in 1851. That number jumped to over 11,000 in 1852. The newspaper, Alta California claimed there were 7,000 to 10,000 Chinese men here by 1853.

American miners in the gold fields almost immediately tried to make it difficult for Chinese to work. In 1850 the state legislature fixed a $20 a month license fee for foreign miners. This law was later repealed, but initially it had Chinese abandoning the mining areas for urban places like San Francisco.

An 1870 law, later deemed unconstitutional, charged a $1,000 fine for bringing subjects of China or Japan into the USA. But some Americans saw them as cheap, reliable labor for the railroads and agricultural interest. By this time, urban Chinese were shopkeepers, laundrymen, and restaurant owners, and rural Chinese were woodchoppers, freight haulers, and railroad construction workers. China Camp in Marin County on San Pablo Bay was home to Chinese fisherman. Mining camps of any size might have a “China Town” for Chinese workers who remained in that industry. In many of these places, a temple or “Joss House” might be erected for worship of Chinese deities.

Eureka in 1885 had a China Town and others existed in Ventura, Fiddletown, Grass Valley, Monterrey, Fresno, Sacramento, and Loomis. Santa Rosa in Sonoma County had a China Town on First & Second Streets. Chinese temples that exist to this day were built in Yreka, Oroville and Weaverville, along with Mendocino City’s 1854 Kwan Tai temple.

The Sacramento – San Joaquin River delta had lots of Chinese laboring to build flood control levees. This was an agricultural skill brought with them from China and put to work on California rivers. The towns of Sherman, Twitchell, Brannan, and Grand Island had levees 15 feet wide at the base, 5 feet at the crest, and varying heights to protect productive farm lands. Rio Vista, Courtland, Isleton, Walnut Grove, and Locke all had Chinese communities.

Today, travelers any place in California – from big cities like San Francisco to tiny former Gold Rush towns – might find reminders that the Chinese were once there. Though many tried to exclude them in our past, the Chinese remain a significant part of the state’s heritage.

The Kelley House Museum’s current exhibit, “The Story of Look Tin Eli: Exclusion and Citizenship on the Mendocino Coast,” is up until July 22, 2019 and shares the story of Mendocino’s Chinese and what happened statewide. Catch this great display Fridays through Mondays 11am – 3pm. Call 707/937-5791 for more information.