Did you know you can find more than 50 different kinds of seashells on the Mendocino Coast? Thanks to the late Dr. Richard White’s publication, “Mendocino Medicine and Gazetteer,” his interest in seashells can be shared 30 years later.

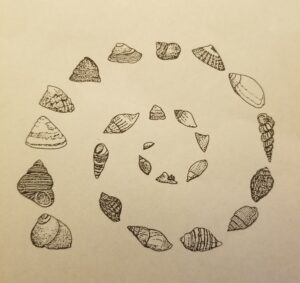

“Seashells of Albion: The Gastropods” was a fascicle (printed installment) in “Coastal Life of Albion.” These were from Dr. White’s personal research, and the collected reports of the Pacific Union College’s Mendocino Biological Field Station, which was located on the south side of the Albion River Harbor. Local artist Jane Russell did meticulous line illustrations to enhance the learning experience. Previous work by the students at the field station were also included in the guide.

Without turning this newspaper column into a science lecture, this writer will stick to the common names, as Latin names for categories of family, genus and species can change over 30 years.

Gastropods are the largest class of mollusks and are related to segmented worms. They have a muscular foot for movement and a radula, a protruding tongue-like organ that allows them to scrape algae from rocky surfaces and do another amazing eating trick. Gastropod shells can be cup-shaped or coiled into whorls.

Abalone are the gastropods that we like to eat. They are herbivores that browse on seaweed, and have shells with holes to discharge wastewater. Thirty years ago, they were common, but now they are scarce. They don’t move around much, which makes them easy prey for people. Researchers have documented that native people picked them off coastal rocks for the last 7,000 years and used the iridescent shells as trade items. There are Flat Abalone, less than five inches long, and Red Abalone up to nine inches in length. Other species include the uncommon Pinto Abalone and the rarely found Black Abalone.

Limpets have conical shells, and the Rough Key-Hole Limpets browse nocturnally. (What? You don’t want to be the researcher out in the dark in the surf line with a flashlight seeing if they actually do move?) Dunce Cap Limpets like to hide in abandoned sea urchin holes. There are also Rosy, Flat, Plate, Ochre, and Brown Limpets.

Black Limpets attach themselves to bigger gastropod shells and feed on algae attached to those shells. Finger Limpets secret mucus between themselves and a rock and can remain out of water exposed to air for long periods of time. Shield Limpets like to live in mussel beds, and Eelgrass Limpets are the smallest at just a quarter inch long.

Turban Snails prefer to live on exposed rocks. There are Costate, Channeled Top, Brown, Red, Dusky, Black, and Dwarf varieties. Periwinkles are under an inch long, and the checkered ones like to hide in empty barnacle shells. Indian Wentletraps are carnivorous and inject a salivary toxin into sea anemones, then tear off the creature’s tentacle tips for a meal.

Hoof and Slipper Shells are described in this report, as are Moon Snails, which are active (rather than staying put) carnivores that plough through sand in search of bivalves to eat. They use their proboscis to drill and rasp through a shell and then suck out the prey through the hole.

Murex Snails feed on barnacles. Dogwinkles are voracious predators of mussels. They also eat their own eggs and their larva eat each other in the egg capsule. Channeled Dogwinkles like to eat oysters and Frilled ones like to eat barnacles. There are varieties of Whelks and a Columbian Amphissa that scavenge on dead animal tissue.

Dr. White’s writings are not without humor. The last Gastropod he discusses was a 1.5-inch Purple Olive. He stated that curtains made of Purple Olive shell beads were a common feature in early Caspar hippie homes.

So, the next time you go beach combing, look with more interest at the seashells you find. Local bookshops have good identification guides to sort them out. Since “Seashells of Albion” is long out-of-print, we’d like to thank Deborah White of Ukiah for sharing her copy.