by Katy Tahja, Kelley House Museum docent

Browsing the shelves of the library in the Kelley House Museum Research Office, I found “Lumberjack Lingo” by L.G. Sorden written in 1969. While it’s focused on how vocabulary was adapted to walking around the Great Lakes states, many of those walkers moved west and brought their terms with them.

Browsing the shelves of the library in the Kelley House Museum Research Office, I found “Lumberjack Lingo” by L.G. Sorden written in 1969. While it’s focused on how vocabulary was adapted to walking around the Great Lakes states, many of those walkers moved west and brought their terms with them.

The cookhouse in a logging camp provided many unique terms. If a logger asked for cackleberries, slush, sow bosom, doorknobs and skid grease, he was asking for eggs, coffee, bacon, biscuits and butter. He might not want bearbait or redhorse for dinner, but gut, firecrackers and fish eggs were fine. Translation: bearbait was meat so old and spoiled you did not want to eat it, redhorse was salted or corned beef, but gut was tasty bologna and fish eggs was tapioca pudding. Oh, and don’t forget the firecrackers — they were cooked beans.

The men who worked in the cookhouse had unique titles, too, along with the food. A belly burglar was a poor cook. Doughboys were kitchen helpers and the hash slinger waited tables. The kitchen mechanic was the dishwasher, the pearl diver washed dishes, and the pot-walloper worked with him.

Life in a logging camp provided challenges. Pants were always under discussion. High-water or staged pants were cut off at the top of high boots, right below the knees. If they were waterproof, they were called tin pants. Get in a fight and you might suffer from loggers’ smallpox. Loggers’ boots had spikes in them, and the imprint could scar your skin if you got stepped on. This happened when you drank too much cougar milk — illegal homemade liquor. Your hat was called a louse cage, and you had to deal with pants rabbits (lice).

Jobs in a logging camp came with their own terms, too. Bull of the woods was the boss of a logging crew. He disliked camp inspectors. These were short-term workers traveling from camp to camp looking for work, getting a free meal, then deciding to move on. Catskinners drove Caterpillar tractors and gandy dancers were the pick-and-shovel men, especially around railroads. Hairpounders were horse teamsters, and a heaver was the fireman on a wood-burning locomotive throwing wood into its fire.

The blacksmiths, known as iron burners, used Irish baby buggies (wheelbarrows) in their work. Ink slingers worked in the offices. They appointed man catchers, men to go out and recruit new workers for the camps. Landlookers were men who could estimate the value of standing timber, and knotbumpers were the men who cut knots off the logs before they were moved. Road monkeys kept the roads going into camp in good shape, tie whackers cut railroad ties from logs and stumps, and detectives looked over clearcuts to measure waste.

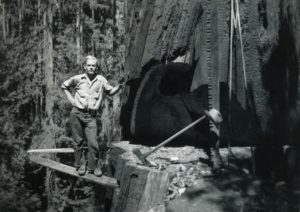

My own father-in-law, Andrew Tahja, was born in a logging camp in Berry Gulch off Highway 20 and as a young boy worked as a whistle punk. Workers on a logging site often cannot see each other and someone with a loud mechanical whistle signals between locations, hence whistle punk.

No matter what job you did, it was not good to be a wood pecker, which meant that you were a poor chopper, or if you had to leave camp wearing a wooden kimono. That last term means you’re dead and in a coffin!

Photo caption: “Whistle punk” Andrew Tahja on a springboard at Ten Mile Camp #3, circa 1937