While many people are familiar with the internment camps for people of Japanese ancestry that the US government established during World War II, few folks realize this was not the only group incarcerated in California. Residents of Mendocino County born in Germany or Italy were also considered “enemy aliens.”

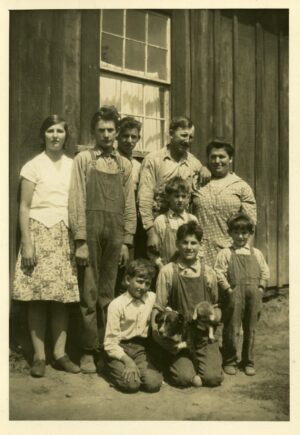

Pete and Rosa Piccolotti posing at their Big River ranch in 1930 with their children: Ida, Fred, Albert, Louis, George, Henry and Earl (not in order). (#2007-03-1446-21, Kelley House Museum)

Starting in 1942, people of Japanese descent were considered threats to national security on the west coast and were forced to leave everything behind – homes, businesses, families – and were removed to internment camps located in California and other sites all over the country until the war was over.

However, when the government looked at the sheer number of Italian and German Americans, numbering in the hundreds of thousands, they realized they couldn’t incarcerate all of them, but they could watch them closely. A Mendocino City family’s travails under this exclusionary regime is shared later in this story.

Then there were the prisoner-of-war (POW) camps established for captured German and Italian servicemen. America’s main allies, England and France, did not have the time, space, or energy to develop and sustain camps. Meanwhile the US had wide open spaces and a need for workers, since most able-bodied men had been drafted into the military. The US helped the worldwide war effort by accepting POWs.

In California there were over sixty-five such camps. German and Italian groups were never mixed – each camp had only one nationality. Detainees were decently housed and fed meals the equivalent of those served American servicemen. They did their own cooking and baking. Italian prisoner groups got more pasta, and Germans received more potato rations.

Larger camps sent small crews with guards to dozens of locations. Prisoners performed a wide variety of work, including logging, agriculture, field work, canning, fish processing, clothing manufacture, work in arms and ammunition factories, and building transportation vehicles for land, sea, and air.

In Northern California, POWs worked in almond groves in Arbuckle, in Auburn on Civilian Conservation Corps projects, and in Tule Lake cleaning irrigation canals for farmers. Crews worked on highway construction, but most work was agricultural.

Now, for the local connection. After the US entered the war, residents from a country we were fighting were immediately under suspicion. In Mendocino County, this generally meant that people of German or Italian descent could not live or travel west of Highway 1.

Not every immigrant had taken the time to obtain citizenship. The Piccolottis, a well-known family who operated a large truck farm fourteen miles up Big River, were affected by this situation and faced many problems.

Pete and Rosa Piccolotti were Italian natives who immigrated to Fort Bragg, married, and had a large family. In 1942 several young Piccolotti brothers went into military service. Meanwhile, the parents were declared enemy aliens and for national security reasons were not allowed west of Lansing Street where the post office and bank were located. Friends helped with necessary errands in town and the Mendosa family delivered the produce the family raised to Fort Bragg for them.

Two Piccolotti brothers died during the war from non-combat health issues. After the war in 1948 Pete and Rosa started studying for the hard questions a judge might ask them during citizenship proceedings. They were sponsored for US citizenship by Joe Mendosa and Ernest Madera.

The big day came, the Piccolotti family and friends drove to Ukiah, and when the judge interviewed them, he asked if their sons served in the military? “Yes! Four of them,” the proud parents replied. That was all the judge needed to hear, no questioning needed. He said, “You are citizens!” A happy ending.

To learn more about this time of California history, read “American Prisoner of War Camps in Northern California,” by Kathy Kirkpatrick, or “Piccolottis, My Life on the Ranch by Big River,” by Alice Piccolotti Ivec. The last title can be read at the Kelley House Museum research library.