In the last half of the 19th century, most of Little River was cultivated farmland, from acres of field crops and grazing land for livestock, to family vegetable gardens. Even in early Mendocino vegetable gardens were grown between houses, with some of the produce to feed the cows and horses, like sugar beets; other crops fed families and the mill workers at the cookhouse. Katie Ford (1857-1944), daughter of Jerome and Martha Ford, wrote about her childhood garden memories: “We used to pull the young turnips and radishes and carrots and go to the duck pond to wash them before eating. Some one delegated to stand on the loose end of the board while we walked out on the end over the water often forgot the importance of their job and we got a dunking.”

In the last half of the 19th century, most of Little River was cultivated farmland, from acres of field crops and grazing land for livestock, to family vegetable gardens. Even in early Mendocino vegetable gardens were grown between houses, with some of the produce to feed the cows and horses, like sugar beets; other crops fed families and the mill workers at the cookhouse. Katie Ford (1857-1944), daughter of Jerome and Martha Ford, wrote about her childhood garden memories: “We used to pull the young turnips and radishes and carrots and go to the duck pond to wash them before eating. Some one delegated to stand on the loose end of the board while we walked out on the end over the water often forgot the importance of their job and we got a dunking.”

The air smelled of barnyards and livestock. The Kent Ranch, a dairy farm, probably had the most cows. There were a lot chickens there, too. Isaiah Stevens had quite a few cows in the pasture where now several llamas graze, next to Glendeven Inn. Wilder and Etta Pullen’s ranch was farther south (where Heritage House is now) and they always had several cows, a few pigs and sheep, and a lot of chickens.

The air was filled with dust from the unpaved roads. Or the roads were muddy. Either way, it required a lot of work to keep clothes, shoes, boots, houses, horses and wagons clean. In pre-electricity times, “Monday Wash Day” was an arduous chore. And if it rained on wash day, imagine having to deal with wet laundry indoors. Some homes had clotheslines in the milk room or pantry or kitchen. Some families had household help; most didn’t. It couldn’t have been pleasant. Then the dried laundry had to be ironed, first heating several heavy irons on the stove, pitching wood into the stove to keep the fire going, probably keeping an eye on the bread rising in the warming oven, and then the children spilled some milk or broke a toy. Oh, what to cook for supper tonight?

The air smelled of smoke. The mills produced a lot of it. Every home and cookhouse had fireplaces and stoves burning wood daily. Fields were readied for plowing by burning off the brush or harvest stubble remaining from hay and oats, necessary crops for all the horses and cows.

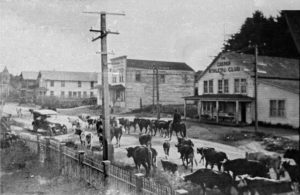

Finally there’s the delicate matter of an indelicate subject — all the byproducts of digestion that was plopped from horses and oxen on the roads. In all the years of reading about local history in newspapers, memoirs, diaries and such, never was there a mention of a sanitation service or recollections of dealing with this unpleasantness, except for a single comment about the farm chore no one wanted — “mucking out the barn.” Of course, such topics just weren’t discussed and certainly were not newsworthy. There was an exception, however, a complaint by residents of Mendocino in the late 1800s of actual animals (cows) roaming loose in the streets. Of particular annoyance were the animals lying down in the road at night that couldn’t be seen in the dark by carriage drivers and pedestrians.

The dust, the smoke, the smells were a natural part of the country life of the hard working Little River ranchers and woodsmen. They weren’t prone to complaining. Thank heaven for the sea breezes.

Photo caption: Cows and their calves driven to pasture on the Caspar Headlands

You can enjoy scenes of early life on the Mendocino Coast by searching our online collection of historic photos at kelleyhousemuseum.org. Or, visit the historic Kelley House Museum, Fridays through Mondays from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. and experience a Mendocino pioneer home. For more information, call 707-937-5791.