Halloween came to America in the 1840s with Irish immigrants whose ancestors knew it by its Celtic name, Samhain. A time to light bonfires, wear costumes, and drive away evil spirits, the holiday captured popular imagination. Jack-o’-lantern, already an American novelty, replaced the carved turnips of yore while fortune-telling games decreed that a girl might discover the name of her future husband on this most spirited day of the year.

Turning that focus to Halloween, we know from newspaper accounts that it arrived in Mendocino County sometime during the last quarter of the 19th century. Known on the East Coast as a time for tricks, many of which were epic and sometimes deadly, Halloween was first enjoyed in the county in private parties held in people’s homes. The Beacon and the Ukiah Daily Journal offer many examples of these early events, emphasizing the good times and appropriate decorum of all concerned. In due course, civic organizations such as the Circle Concordia, the Rebekkahs, and others expanded these early celebrations until Halloween was acknowledged in most towns throughout the county.

But, wholesome activity was not enough to quell the original nature of the day and on the coast, the theft of gates, removal of vehicles, and the tipping over of outhouses (in use or otherwise) were popular pranks. Other common activities involved soaping windows, ringing bells, stealing fences. Pranksters in Mendocino took apart a wagon and placed it on top of Tom Shelton’s blacksmith shop while in Ukiah, the preacher’s buggy was placed on top of the church and a cow tied to the church bell to raise an alarm into the night.

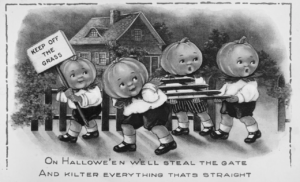

While some laughed off these youthful hijinks, the problem locally and nationwide was a serious one. Mixed messaging in books and other print media made light of stolen gates, a popular theme in Halloween postcards and in some places Halloween was called “gate night.” The pattern of destruction ebbed and flowed, prompting the Beacon to comment in 1907 that “Innocent Fun, when not made at the expense and disturbance of sick and helpless people, is to be commended but Hallowe’en night there seemed a total disregard on the part of some to observe the proprieties of the spirit of Hallowe’en. Things were done that night which should shame the perpetrators.” A later warning stated that it was a State’s prison offense to tamper with the town’s fire alarm system.

By 1924, county leaders were aware that police alone could not quell the vandalism. Appeals to better judgment and common decency had failed. In 1928, Ukiah hosted its first Safe and Sane Halloween, marking a renewed effort to supervise and distract youthful wrongdoers. But, the problem was not an easy one. In 1930, the Galloway School south of Point Arena was so badly damaged by Halloween pranksters that it was closed, as the furniture was destroyed and all of the outbuildings pushed off of their foundations. Nine years later, similar damage was done to the local schools and businesses when plate glass windows were “slashed” in Ukiah. Near Laytonville, a private bridge was burned on Halloween night by a twenty-one-year-old man entertaining a group of teenage onlookers. Not surprisingly, at times hot tempers erupted and in 1951, a case went to trial in Ukiah in which a resident fired a shotgun at a group of children. After a short deliberation, the defendant was found not guilty.

As locals applied their wits to the issue, a carrot-and-stick approach emerged. Businesses and organizations such as the Rotary, Boy Scouts, firemen and police joined parents, teachers, and church leaders in funding wholesome alternatives. With the enforcement of curfews, Ukiah police vandalism dropped by sixty-five percent. Later, with the end of the Depression and post WWII end of rationing, trick-or-treating took on the highly sugared form we know today.

High schoolers were encouraged to find alternative activities and for many years, the Sophomore Class at Mendocino High School hosted a well-attended Halloween Party which the Beacon promoted and praised. “Spook Insurance” was sold by the Ukiahi Wildcat Band who offered to clean up messes made by revelers for the nominal sum of $1 per household or $5 per business and was limited to messes made by eggs, tomatoes, water balloons, pumpkins, and shaving cream. Later refinements included the removal of toilet paper, and all proceeds were used to fund the high school band.

The Kelley House wishes you a happy and safe Halloween.